“To be ignorant of the lives of the most celebrated men of antiquity is to continue in a state of childhood all our days.”

- Plutarch

The humid paradisal island was invaded in July. The fierce defenders had lost their colonies in North Africa, and now they faced multitudes of attackers were out to take their precious Sicily. The invaders made their amphibious landings upon the beaches in the earliest hours of the day, some diverted by the large curtains of wind sweeping them to different points of the island.

The General stood upon the take beneath the glimmering rays of the Italian sun which reflected off his shimmering helmet and white revolver. He imagined himself as the reincarnation of Hannibal, one of his heroes from the ancient world that he reenacted as a child. General George S. Patton (1885-1945) stood victorious following the capture of Palermo.

The ultimate objective was the city of Messina, a port city directly across from the peninsula of Italy. Patton and the Americans were ordered to let British General Bernard Montgomery travel the main highways, and to secure the rest of the island as the British marched to take all the glory.

Patton, like the rest of the Americans, was tired of taking the back seat to such a prideful and condescending general. Patton in Palermo was on the northwest side of the island, Messina is at the northeast side, and Montgomery was south, advancing up the eastern shore. Patton had a clear shot across the northern shore with only one thing on his mind: win the race.

Like Hannibal and his elephants, Patton rallied his men and their tanks. They galloped across the northern shore with lightning speed. There wasn’t a Sicilian stronghold that could stop them. Like Scipio studied Hannibal and defeated him, so had Patton studied Rommel in North Africa and defeated him. It was as if Patton came to Sicily with the ancients seeking revenge.

And in short order, Patton and the Seventh Army captured Messina, and they were there 10 hours by the time Patton stepped out to welcome General Montgomery to the city.

What To Do

Patton was a voracious reader. Though he slowly became one over time, as a young boy, he loved the stories from history. He reenacted scenes from The Iliad, The Odyssey, Shakespeare’s historical plays. In them Patton saw himself, believing that the same spirit of the warriors from the past was in him.

This love of history and books brought him through the darkest period of his life. During the heavy campaigns of 1944-45, he had relied on the Bible, a book of prayer, Caesar’s Commentaries, and a complete set of Kipling. He drew from them the steps of exactly what to do next.

Patton’s biographer, Martin Blumenson says this:

“They imbued in him the importance of character. Those who made moral choices succeeded, he learned, while those who sacrificed honor for expediency failed and merited disgrace. Historical figures instructed him in the military profession. Scipio and Hannibal in North Africa showed a thorough grasp of soldiering, along with personal courage and the intuition to be at the critical place at the crucial moment. Caesar to the Tenth Legion in Gaul, Joan of Arc at Orleans, Napoleon to his Army of Italy provided personal and dynamic leadership, together with direct inspiration that touched every man under arms. Stonewall Jackson gave his followers the willingness to beyond the limits of endurance and to accept the risk an the prospect of disfigurement and death. These commanders who exhibited self-confidence, enthusiasm, and bravery became his models, and he absorbed their genius.”

Biographies and the stories of great men carry with them a flame that may either burn the bearer or enlighten his path. Like Patton, if you carefully observe and consider, life lifts its fog and opens its gates to you, revealing great the treasures of what to do. In the past are the pieces to the puzzle, secretly hidden; all you must do is find them.

What Not To Do

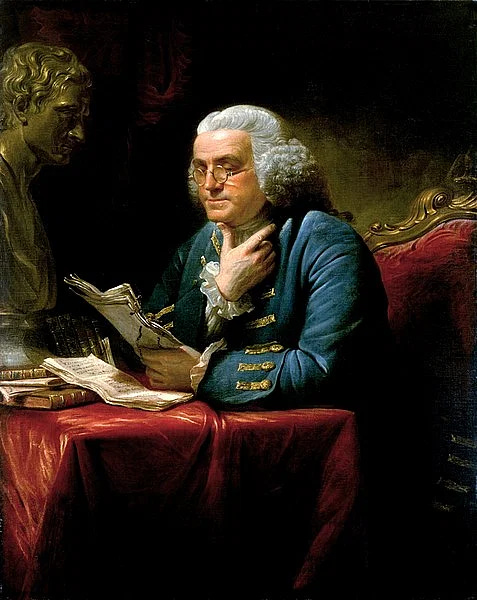

In 1722, a young Benjamin Franklin (1706-90) was an apprentice at his brother’s independent newspaper in Boston, the New England Courant. Here he was exposed to all things writing. He became enamored with books and quickly discovered he wanted to “be a tolerable English writer”.

Franklin began taking successful essays and rewriting them into new forms and arguments. By being in such close proximity to publishing power, he naturally wanted to try his hand at it. But his brother James refused.

Benjamin had to get his work published under his brother’s nose, so thus Silence Dogood, the talkative rural widow was born. He began slipping his writings under the door at night, and being convincing enough, his brother James published them in the Courant.

The Dogood essays became the most successful section of the paper. Full of naïveté, Benjamin revealed the true identity of Ms. Dogood, thinking that James would be proud and embrace him in a new light, but nothing was further from the truth. His brother became even colder and more abusive towards him, leading Benjamin to runaway from Boston.

Philadelphia became his new city to conquer and to make a name for himself in. He found work at the print shop of Samuel Keimer, where he proofread and even wrote pieces for the paper. Like Boston, Franklin’s writings became a hit, gaining him an admirer in the Pennsylvania governor, William Keith.

Franklin and Keith became instant friends, and as an admirer, Keith wanted him to procure a print shop of his own. After a time, Keith informed Franklin that he had notes in London waiting for him so that he may go and purchase printers for his shop. Believing Keith, Franklin abruptly quit his job at Keimer’s, and sailed for London.

When he arrived, he learned the truth: William Keith had a wonderful gift of flattery and exaggeration. There were no notes waiting for Franklin. Being across the globe without any money, he threw himself into work and forgot about Keith.

The print shops in London had a custom unlike those in the colonies. Five times a day they would stop to drink beer. Now young Franklin had resolved himself to be a man of temperance and virtue, thinking that in this he may obtain salvation, so he kept to his oat-water mixture and refused to contribute to the beer fund. The workers took umbrage with the American, but Franklin had been a practitioner of the Socratic method, so he calmly explained his position, and they relented and stopped harassing them.

Suddenly he found errors in passages he already proof read. There was talk of a “ghost” moving the typeset at night. Franklin’s naïveté came to end. He accepted his circumstances and began contributing to the beer fund.

Biographies have extraordinary insight into what not to do. In them we see fragments of ourselves and our faults. They show us how stubborn, naïve, stupid, or lazy we can be. By learning from the faults of others we save years of heartache and struggle by seeing what not to do.

Who To Become Like

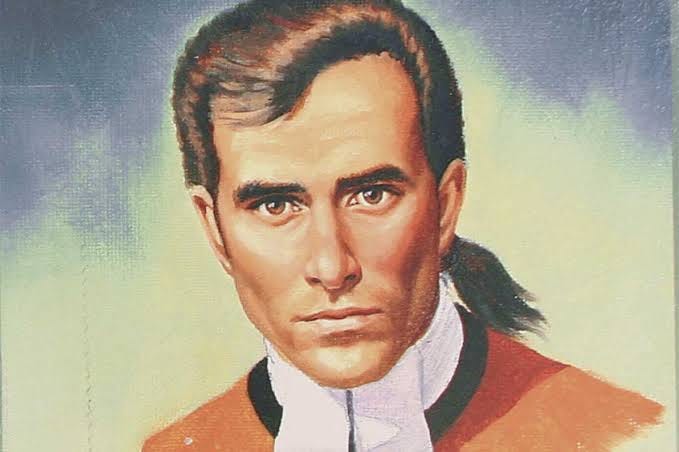

In the spring of 1747, Jonathan Edwards (1702-58), the famed preached of the Great Awakening, was in his study in Northampton, Massachusetts when a young man came on horseback into the yard. He did not seem familiar to him, but as he introduced himself, then Edwards remembered that they had met before only once and that he knew of his efforts in most recent years.

David Brainerd (1718-47) was a young Presbyterian minister and missionary to the Native Americans, who at this time had been laboring for 4 years and was sick with tuberculosis. This meeting with Edwards at the end of his life would prove useful and edifying for the rest of the world.

A few years before in the winter of 1741-42, Brainerd was converted during the Great Awakening as a student at Yale. Full of zeal and new-found love, Brainerd became very serious about his faith, but not without fault. He criticized the spiritual life of one of his tutors and was expelled. Brainerd was convicted of his arrogance and was humbled. He apologized to the tutor and to the school, recanting his comments with sincerity, but Yale did not accept him back.

But for Brainerd, he had already interviewed with Presbyterian ministers in New York as a missionary candidate to the Indians, and was slated to begin work in April 1743. The passionate Brainerd was assigned to Stockbridge, which was at the time on the borders of Massachusetts and New York. He gladly went with the charge, excited about the opportunity to bring the Gospel to the Indians, but soon that passion would dwindle to a flickering flame.

After a year of studying the language and interacting with the Indians, there had been no sign of a difference being made. Brainerd had frequently traveled to Stockbridge on horseback, riding over 20 miles one-way. His love for the Indians would cause him to stop to pray, kneeling in the snow. After such fervent prayer, Brainerd would rise to see that the heat from his body had melted the snow in a 2 foot diameter underneath him. Even through with this love, there was no difference. After this first year, he received a call to a pastorate, but declined in order to preach where the Gospel had never been preached before.

Brainerd was sent from Stockbridge to the Indians on the Delaware River. Here he lived his Spartan lifestyle of traveling long distances on horseback to preach, and he slept on the ground out in the woods.

Brainerd traveled to and fro in the region preaching and praying, but there was again such little signs of change. Iain Murray says “he was ‘sometimes much discouraged and sunk in his spirits through the opposition that appeared in the Indians to Christianity’”. To Brainerd this seemed to be the end of his efforts.

Suddenly, it was as if thunder had roared through the trees, waking the souls of the Indians. In the summer of 1745, Brainerd saw in New Jersey the changes in the Indians that he once saw in himself. He wrote of them: “I have oftentimes thought that they would cheerfully and diligently attend divine worship twenty-four hours together if they had an opportunity to do so…I know of no assembly of Christians where there seems to be so much of the presence of God, where brotherly love so much prevails…”

Brainerd had a new found strength that summer, and by November, he had ridden over 3,000 miles on horseback. He labored like this for another year, seeing multitudes of Indians coming to Christ, and had to baptize as many as 14 at a time. In the winter of 1746-47, he became sick, which limited his efforts, not fully stopping until he reached the stops of Jonathan Edwards’ home in Northampton.

After Brainerd died, Edwards published The Life and Diary of the Rev. David Brainerd. Murray writes this about Edwards’ reasons behind making this man a well-known figure: “He wanted Brainerd to be read and known not simply as an example of a true missionary but as an example of a real Christian, showing what the power of godliness and ‘vital religion’ truly is.”

It was this first-ever full-length missionary biography that gave way to the missionary movement of the 19th century. The missionaries traveled across the globe into Africa, the Middle East, and Asia carried with them the biography of Brainerd that had inspired them to go. William Carey, the famous missionary to India, and his fellow missionaries wrote in their famous ‘Covenant’ the phrase, “Let us often look at Brainerd.”

History is full of very bad men who were only out for their own good, bending and manipulating everyone and everything through their devices. Their great destructive efforts mar and twist our perspective. But when someone as rare as David Brainerd comes around, you take notice, you make sure you don’t miss what you’re seeing.

These are the types of men that change other men. Biographies have their power in showing you who to become like. May the lives of good men exert their power on you.

Necessary Transformations

He had been traveling and publicly performing since he was 5 years old. It was 1781 and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-91) was now 25. The road had been tiring and monotonous. Mozart had to perform for the same types of people, rich aristocrats and royals, under the control of his father, who had begun to rely on him as his only source of income.

Mozart’s struggle was that he loved to play the piano. As a beginner he quickly surpassed his older sister, perfecting pieces that she struggled with. His parents had to peel him off of the piano bench to put him to bed. While playing with others, he would have his friends play games set to music just so that he could get behind the piano. When he began touring, he would often become moody and distempered in ways that his parents could only handle by letting him play the piano. It was with this love and talent, that appeared to have come from heaven, that his father used in order to dress him and his sister up to perform for the lucrative courts of Europe.

As years went by and as the ivory keys made their sounds, Mozart began to despise performing. He would feign sickness and exhaustion to get out of performances, no matter how far they had traveled. Even worse, the money slowly dried up, causing his father to become more desperate until he secured for his son a position in the court of the archbishop of Salzburg, their hometown, as a court musician. This he loathed more than anything else.

Mozart was limited by what he could play and compose, and he was treated as dispensable by the archbishop. This was an insult and a disregard for his abilities. He had performed in greater courts before greater people. Mozart’s father held his grip here the tightest. He became disgusted and frustrated when his son presented a composition more in line with his own preferences, throwing them away, and scolding him. Mozart was forced in line by his father. Losing this job would mean ruin for his father.

The music that Wolfgang had ingested over the previous 20 years began to rise to the surface. He could not stop thinking about composing operas. As a boy, he dreamed that this would be his life’s task. But being in Salzburg was limiting as it did not have opera houses; they would be in Vienna. To have any chance of doing what he felt he must do, he had to leave.

Mozart abruptly resigned as a court musician, causing a permanent tear in his relationship with his controlling father, and moved to Vienna. For the first time in Mozart’s life, he could make decisions for himself. The opportunities were vast and his creative powers could now be tapped into. He began composing vigorously.

In Vienna, he changed music forever by writing music for larger orchestras, restructuring symphonies, and created sounds in operas that had never been heard before. It was this necessary transformation that is responsible in marking his place in history. If he had never left Salzburg, he would not even be a footnote in history.

Conclusio

Biographies contain the power to show you what to do, what not to do, who to become like, and in making the necessary transformations in yourself. They shape and instruct through both subtlety and clarity.

When you take up and read, you will find that this power appears as if it cannot be described, but felt. When General Patton took his Seventh Army to Germany he must have known this keenly when he said, “I entered Trier by the same gate Labienus used and I could almost smell the sweat and dust of the marching legions.”