Lead Like Colonel Glover Johns

A Leader’s Leader

In the colossus of an autobiography, About Face by Colonel David Hackworth, one is to find stories of guts, grit, glory, and wisdom. These stories flow naturally from the autobiography of a legendary soldier who was orphaned, and who forged military papers at 14, fought in both Korea and Vietnam, received 8 Purple Hearts, and led some of the greatest Army Divisions ever.

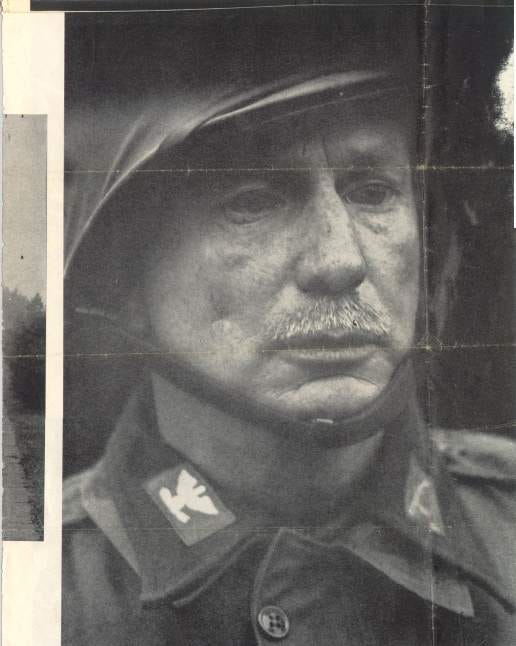

But legends are not formed, or are generated, overnight. They are molded. Shaped. Hackworth is a legend and may be the greatest Infantryman the United States has ever produced. He would not have the legacy he has today if it weren’t for one man, Colonel Glover Johns.

Colonel Glover Johns is unveiled following Hackworth’s dismal station at Nürnberg, Germany in the late 1950’s and early 1960’s. After the funereal atmosphere of the Nürnberg post, one full of corruption and immorality, Hackworth is ordered to report to the post at Mannheim. Here he meets one of the three men he would later dedicate his autobiography to. Glover Johns, General George S. Patton’s aide prior to World War II, as a battalion commanding officer led the task force that captured the pivotal French town of St. Lô, later recounting this in his book The Clay Pigeons of St. Lô. Hackworth tells a story. When Johns was the executive officer of the 40th Infantry Division in Korea, Johns had “gotten down on his belly in the mud to check the unit’s machine-gun field of fire, and promptly moved two-thirds of the MG bunkers that had sat there for two years.” He was a man whose shadow was mightier than most men.

Colonel Johns was the right man at the right time, to become to Hackworth, the shining, bright officer, the father he never had. Johns delivers killer line after killer line, causing the reader to be at the ready with his pen in hand to underline away. The chapters he is in is simply worth the price of the book. Nearing the end of Part I in About Face, in Johns’ retirement speech he gives his men the following:

[Excerpt from About Face by Colonel David Hackworth]

“Johns was a leader who taught by example, so most of the points he made weren’t exactly new to us. But to hear in a single speech this great man’s basic philosophy of soldiering was like being let in on the secret ingredients of some magic formula. To wit:

Strive to do small things well

Be a doer and a self-starter—aggressiveness and initiative are two most admired qualities in a leader —but you must put up your feet up and think.

Strive for self-improvement through constant self-evaluation.

Never be satisfied. Ask of any project, How can it be done better?

Don’t overinspect or oversupervise. Allow your leaders to make mistakes in training, so they can profit from the errors and not make them in combat.

Keep the troops informed; telling them “what, how, and why” builds their confidence.

The harder the training, the more troops will brag.

Enthusiasm, fairness, and moral and physical courage—four of the most important aspects of leadership.

Showmanship—a vital technique of leadership.

The ability to speak and write well—two essential tools of leadership.

There is a salient difference between profanity and obscenity; while a leader employs profanity (tempered with discretion), he never uses obscenities.

Have consideration for others.

Yelling detracts from your dignity; take men aside to counsel them.

Understand and use judgement; know when to stop fighting for something you believe is right. Discuss and argue your point of view until a decision is made, and then support the decision wholeheartedly.

Stay ahead of your boss.”