“Be still, my heart; thou hast known worse than this. On that day when the cyclops, unrestrained in fury, devoured the mighty men of my company; but still thou didst endure till thy craft found a way for thee forth from out the cave, where thou thoughtest to die.”

Enraptured with the affections of Mrs. Carpenter, he soothed his frequent tears with her seduction, only to sense deeper the pains of an odyssey in a foreign land and the agony of perdition: the price to pay for despising the lotus and recalling to mind his home.

Entranced by this goddess from Mississippi, he pursued her until she relented. Faulkner had been gone from home 3 years, and lacked kinsmen amongst the foreigners. So he was Carpenter’s suitor as his wife and daughter laid in an interlude, waiting for his return home. As their sensual desires enflamed, Faulkner would write her poetry, and adorned their hotel beds with gardenia and jasmine petals. His Calypso would later call him the love of her life.

Night after night, he would meet her for supper. And on the weekends when he was out of the studio, away from writing screenplays, they would go down to have picnics at the beach. As the waves of the Pacific recurred in his ear, he drifted into deep thought, and mused only of getting back home to Rowan Oak.

William Faulkner was 33 years old when he purchased Rowan Oak. This antebellum plantation house in Oxford, Mississippi was dilapidated then, needing much repair as it had been abandoned for many years. Faulkner was an aspiring writer with two unsuccessful publications to his name when his novel The Sound and the Fury became a hit in 1929. It was from this achievement that he was able to purchase this home of the Greek Revival the following year.

Faulkner, acquainted with his Scottish lineage, planted a rowan tree in each corner of the property as it was done in time past to ward off evil spirits. He and his new wife, Estelle, would do most of the repairs themselves. They jacked up caving floor, fixed the broken windows, replaced the wooden beams, restored the walls, and reinforced the pillars. For Faulkner, preservation and carrying the past forward was a way of life, and so Rowan Oak quickly became his Ithaca. He settled down in his home as a man who wanted to stay put, though imminent circumstances would determine otherwise.

Following the success of Light in August in 1930, he began writing Sanctuary, and published it in 1931. His publisher, Cape & Smith, had promised to pay him $4,000 for the novel, but suddenly he received word that the company went bankrupt, as it was common in the days of the Great Depression. Because of debts of his own, Faulkner quickly ran out of money. Talk spread quickly around Oxford that their local author was broke. When Faulkner went into the sporting goods store to purchase shells for a hunting trip, he tried writing a $3 check, but the owner refused, and asked for cash instead.

In the midst of this shame and destitution, he received a wire from a talent agent at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, MGM, offering him $500 a week to write screenplays in Hollywood. The Southerner, strapped with debt and infused with the love of home, had no other choice to make. He accepted the offer, but couldn’t even pay for a wire back. MGM advanced him the money, and paid for his departure.

As he arrived in Babylon, he later recalled that the words of Dante’s Inferno rung in his ears, “Abandon hope, all ye who enter here.”1 He would be in Hollywood, off-and-on, for 20 years.

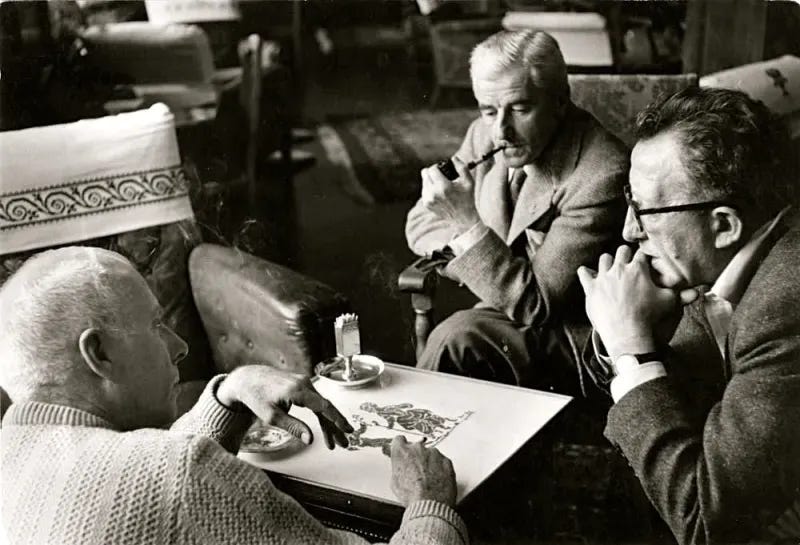

Faulkner became one of Howard Hawks’ best assets. His first script for him was completed in 5 days, which would star Gary Cooper and Joan Crawford. Together they made hit after hit. When Hawks would hit a wall professionally, he would call Bill Faulkner for help. While this on-screen relationship began to bloom, his off-screen relationship with Meta Carpenter, Hawks’ assistant, began to bud.

During his marathon in Hollywood, he became acquainted with big stars, such as Clark Gable, often partying or hunting with them. He found his crevices in California: ones that reminded him of home. They were places that helped him think and void of the incessant sounds of a greedy city. His sadness was repressed by floods of alcohol. Nights of drinking turned into days of drinking. Faulkner went on a 10 day bender around Los Angeles, walking around the city with only one shoe. Hawks and others intervene.2 Neither great stars nor solaces were going to pay off all his debts, it had to be big hits.

After several years of success in La-La Land, he was approached by Hawks for their most ambitious project yet, Battle Cry.

“I am writing a big picture now, for Mr. Howard Hawks, an old friend, a director. It is to be a big one. It will last about 3 hours, and the studio has allowed Mr. Hawks 3 and ½ million dollars to make it, with 3 or 4 directors and about all the big stars. It will probably be named ‘Battle Cry.’”3

These were the days of World War II, and this dynamic duo were set on striking the iron whilst it was hot. They headed off to the Sierra Nevada to begin, and two weeks later, Faulkner had the first 143 pages written. By the end of the summer, the author of growing fame had completed it. There was much confidence from Faulkner:

When I come home, I intend to have Hawks completely satisfied with this job, as well as the studio. If I can do that, I won’t have to worry again about going broke temporarily…. This is my chance.”4

With a director who had several hits to his name and an author who was contemporaneously writing best-selling novels, the studios had much advertising fodder at their hands. Faulkner had in mind two rising actors to play the lead roles, Henry Fonda and Ronald Reagan. But because of the large budget that grew rapidly the project was cancelled, and never saw the light of day.

All seemed lost to Faulkner. The journey looked as if it would go on forever, and he was never to return home. But the author’s voyage did not end between a rock and a hard place. As he was writing screenplays in Hollywood, he continued writing novels such as Absalom! Absalom!, The Unvanquished, The Wild Palms, The Hamlet, and Go Down, Moses. But none of these had more freeing results for Faulkner than Intruder in the Dust, which went on to win the Nobel prize. Because of the great commercial success, MGM green-lighted it as a movie. It was filmed in Oxford, Mississippi and had its world premiere there as well. From this, Faulkner eventually had the financial means to come home.

Years later, shortly before his death, Faulkner was tending to his garden. One of the old peach trees of the grounds that had been there for almost 100 years, surviving the burning of Oxford, was beginning to droop. Faulkner’s instinct of preservation was fulfilled when he took an old cedar post to support it. This man of ancient heart held fast to the pillars and props of history, as he had to do time and time again, in order that he might endure and prevail.5

Ibid